How NAEP’s Oral Reading Fluency Study Informs Literacy Instruction

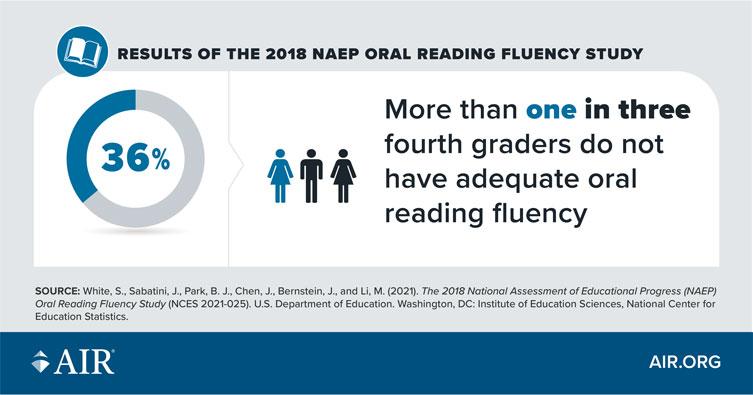

In recent years, about a third of fourth grade students have performed below the NAEP Basic level in reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the Nation’s Report Card for what students know and can do in various subject areas. The 2018 NAEP Oral Reading Fluency Study now provides insights into why reading can be difficult for students beyond the early elementary years.

In this Q&A, AIR Senior Researchers Bitnara Jasmine Park and Abigail Foley and Senior Technical Assistance Consultant Rebecca Bates discuss the findings of this study, which were released in 2021. They also offer their insights into how policymakers, education leaders, and teacher preparation and professional learning programs can use the findings to strengthen literacy instruction.

The National Center for Education Statistics conducted this study to examine fourth graders’ ability to read passages out loud with sufficient speed, accuracy, and expression, as well as the foundational skills of word reading and phonological decoding to gauge underlying sources of poor fluency. Oral reading fluency and foundational skills are important components of reading that are necessary for successful reading comprehension.

Because the NAEP reading assessment measures reading comprehension only, the Oral Reading Fluency study provides valuable supplemental information about students who have difficulty in reading comprehension. The NAEP reading assessment reports results at the NAEP Basic, NAEP Proficient, and NAEP Advanced achievement levels; the Oral Reading Fluency study provides a closer examination of performance below the NAEP Basic level.

A nationally representative sample of about 1,800 fourth graders from 180 public schools participated in the Oral Reading Fluency study. AIR provided technical assistance in the development, data analysis, and reporting for this study.

Q. What are some takeaways from the NAEP Oral Reading Fluency Study?

Park: This study is getting a lot of attention, particularly after NAEP reading scores in grades four and eight declined nationally from 2017 to 2019. Looking at the results, here are three key findings:

- There is a consistent and positive relationship between the NAEP reading assessment and oral reading fluency and foundational skills. Students with higher scores on the reading assessment perform well on oral reading tasks, while students with lower scores on the reading assessment have difficulty performing oral reading tasks.

- There is a noticeable variation in oral reading fluency and foundational skills among students performing below the NAEP Basic level. A major objective of this study was to provide a nuanced picture of the reading performance of low-performing readers. For the first time, the study provides breakdowns for three sublevels within the below NAEP Basic achievement level. Students who struggle with reading are not all the same. Their skills vary considerably.

- There is an inadequate development of foundational skills necessary for fluent oral reading and comprehension among students performing below the NAEP Basic level. This is cause for concern. Reading comprehension is critical for learning across the disciplines, as students move up the grade levels.

Bates: What really stands out to me are the disparities in performance by race, gender, economic status, English learner status, and disability status. What are we not doing right for these kids? If we truly value all students and want them to succeed, reading is the great equalizer.

Q. Can you describe how a child with inadequate foundational skills would read a passage aloud, read words, and decode words?

Foley: A child who struggles with reading usually struggles with accuracy—reading words correctly. When they come across an unfamiliar word, they might skip the word or guess at it. They might recognize the first letter, which reminds them of another word with a similar first letter. They might take a guess based on familiar parts of the word and misread it. Students who struggle with fluency might read a little robot-like or choppily, so it doesn’t sound connected. That can also impact their ability to successfully read a passage and understand what it’s about. They also might lack expression—rhythm and intonation. All of these components of oral reading fluency—accuracy, reading rate (words per minute), and expression—will definitely be affected if a student struggles with decoding.

Fourth graders who struggle to read grade-level text have often memorized high-frequency words without understanding that words are made up of letters that represent sounds. They can hide some of their difficulties and read quickly and accurately. But when you have them break down a word, like a nonsense word or pseudoword, you can see that they lack some of the earlier foundational skills of phonemic awareness and decoding.

A child who struggles with reading might also rely on pictures that may accompany the passage or text, rather than try to read an unfamiliar word and apply their skills. This is not a strategy they can rely on as they get older because more advanced texts have far fewer pictures.

Q. The report on the Oral Reading Fluency study called for a “solutions-oriented discussion” and “a fresh and intensive look at instructional programs,” especially for Black and Hispanic children. What would you advise states, districts, and schools to do?

Foley: While they are tasked with making decisions about curriculum, programs, professional development, resource allocation, scheduling, and other factors that can support teachers and impact literacy instruction, principals and assistant principals aren’t necessarily prepared with the content knowledge to do so. AIR’s work with the U.S. Department of Education’s Lead for Literacy Center focuses on building school leaders’ capacity to improve how teachers can implement evidence-based literacy practices for students with, or at risk for, disabilities that affect literacy. We help them understand essential reading skills; build literacy teams and surround themselves with coaches, special education directors, or grade-level team leaders; and provide tools that can help them identify effective reading instruction.

The Oral Reading Fluency study’s focus on low-performing students also can inform small-group instruction, such as teaching fluency in a small-group lesson. Whole-group reading instruction at Tier 1 cannot be the standard for all students. School leaders and teachers can use data to design blocks of small-group instruction that focus on similar or different foundational skills, depending on students’ needs. Peer-assisted learning programs, which are specifically designed to pair a lower-performing student with a higher-performing student, can be a very effective approach that supports both struggling and advanced students.

Bates: AIR also provides technical assistance to states through the U.S. Department of Education’s Striving Readers and Comprehensive Literacy State Development grant programs. We help state departments of education understand the research on reading and evidence-based strategies to support them.

Many states are doing great work. Mississippi, one of the few states with significant growth on the NAEP reading assessment, has focused on making sure teachers understand the science of reading and developing their knowledge and skills to teach reading skills explicitly. The U.S. Department of Education’s Regional Educational Laboratory Midwest and Great Lakes Comprehensive Center supported Ohio’s evidence-based clearinghouse of strategies for use in an intentional cycle of continuous improvement. (AIR manages REL Midwest and previously managed the Great Lakes Comprehensive Center.) Wisconsin has some good resources to support disciplinary literacy.

There is an opportunity to use American Rescue Plan funds to support effective literacy instruction.

Q. What implications are there for teacher preparation programs?

Bates: Reading is complex. The science of reading is complex. In 2000, the National Reading Panel identified five essential components of reading—phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. There’s been a lot of legislation, policy, and systematic instruction around a “simple view of reading,” defined in this formula: decoding x language comprehension = reading comprehension. But the science of reading has evolved. Researchers are urging us to focus on other important elements of reading, including executive functioning and working memory, morphology (word parts), specific ways of reading across the disciplines, and culturally responsive teaching.

Foley: It’s so important for preservice teachers, particularly early childhood and elementary teachers, to enter the classroom with a solid understanding of how important teaching foundational skills is to reading comprehension. Some states and teacher preparation programs are doing great work around teaching literacy across the curriculum and across the disciplines. Right now, I’m working with Rhode Island, which is bringing together its universities to think about the extent to which they are teaching literacy and the science of reading in their programs. They know it’s not enough just to bring the reading teachers together. This is a conversation that needs to involve faculty across programs and across disciplines, as well as state education agency stakeholders.