In Conversation: What Do Rising Rates of Anxiety and Depression Mean for Families, Schools, and Communities?

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented American families with extraordinary challenges. Alarming rates of anxiety and depression symptoms are among the most troubling.

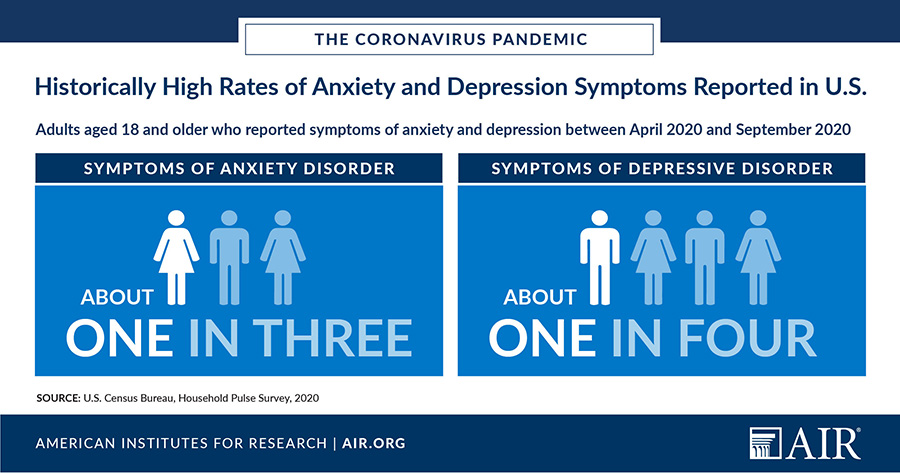

As part of AIR’s COVID-19 response to support educators and health and human service providers with evidence-based practices, AIR researchers analyzed data on anxiety and depression captured in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, a new biweekly instrument measuring household experiences during the pandemic. The key takeaway: Reported symptoms of anxiety and depression are extremely high by historical standards.

Earlier this year, the federal government began administering a Household Pulse Survey monthly to gauge how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting individuals, including their mental health. According to this survey, about one in three adults aged 18 and older have reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety and about one out of every four have reported symptoms of depressive disorder between April 2020 and September 2020. While a direct earlier comparison is not available, the National Health Interview Survey shows much lower rates of reported anxiety and depression symptoms experienced between January 2019 and June 2019 (8.2% and 6.6%, respectively).

AIR’s Senior Finance Specialist Frank Rider and Senior Technical Assistance Specialist Kelly Wells discussed the implications of these findings for families, schools, and communities. Rider helps states and communities develop systems of care for children and youth and their families. Wells supports schools and communities in developing, implementing, and sustaining evidence-based, child-serving programs in school and community settings.

Q. How might the extremely high rates of anxiety and depression symptoms affect parents and children this school year?

Wells: It is worth noting that there might be some disconnects between parents and students on how they are coping. For instance, I know a school district that recently conducted a moment-in-time survey of 3,000 students and their parents. A high percentage of students said they were anxious about starting school. They were lonely. They were worried about what the future holds. On the other hand, most parents said, “Everything is fine,” and their child is adjusting well.

Wells: It is worth noting that there might be some disconnects between parents and students on how they are coping. For instance, I know a school district that recently conducted a moment-in-time survey of 3,000 students and their parents. A high percentage of students said they were anxious about starting school. They were lonely. They were worried about what the future holds. On the other hand, most parents said, “Everything is fine,” and their child is adjusting well.

It’s also important to recognize inequities in mental health. AIR’s analysis of the pulse data found that anxiety and depression disproportionately affect younger, minority, low-income, less well-educated adults, who may be more exposed to the virus because many are front-line workers. We also have many racial equity and social justice issues playing out in the world. Many students are paying attention to this—and there’s probably a lot of trauma among children who never faced trauma before. We don’t have a crisis response manual to deal with all of this.

Rider: Kelly is right. Even kids who were well-adjusted are experiencing mental health issues during the pandemic, which has exposed vulnerabilities in many more people. COVID-19 has caused major economic devastation, separated many children and families from community resources and support systems, and created widespread uncertainty and panic. Some students are in families that have been very directly affected by the virus and some perhaps have experienced the death of a family member. Some are in families where someone lost their job, and family income is now significantly lower. The stress can certainly precipitate neglect, verbal and emotional abuse, or domestic violence.

Rider: Kelly is right. Even kids who were well-adjusted are experiencing mental health issues during the pandemic, which has exposed vulnerabilities in many more people. COVID-19 has caused major economic devastation, separated many children and families from community resources and support systems, and created widespread uncertainty and panic. Some students are in families that have been very directly affected by the virus and some perhaps have experienced the death of a family member. Some are in families where someone lost their job, and family income is now significantly lower. The stress can certainly precipitate neglect, verbal and emotional abuse, or domestic violence.

There are things we can do to help. We can use mass media, social media, and formal communication networks—in law enforcement, health care, education, and public health sectors—to alert those who experience abuse that help is available. Schools could offer virtual counseling or telephone check-ins. Health care providers and educators should be encouraged to screen parents and students for intimate partner violence and child abuse. We can work with law enforcement and other state and local personnel to understand that stay-at-home orders need to be relaxed when the home is unsafe.

Q. What are some implications for educators and schools, particularly as they implement distance learning?

Bringing Into Focus: Addressing Students’ Immediate Mental Health Needs as They Re-Engage for the 2020-2021 School Year

Webinar recording

Presentation slides

Understanding Student Mental Health Needs and Building a Framework for Comprehensive School Mental Health Services

Webinar recording

Presentation slides

Supporting Student Mental Health From a Distance: High-Tech and Lo-Tech Approaches to Support Students Where They Are

Webinar recording

Presentation slides

Selecting and Implementing School Mental Health Programs

Webinar recording

Presentation slides

Developing the School Mental Health Workforce

Webinar recording

Presentation slides

Developing a Trauma-Sensitive School Mental Health Approach

Presentation slides

Rider: Even before the pandemic, about one in every five students on any given day came to school with a mental health issue that affected their learning, according to federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. This could be anything from attention deficit disorder, anxiety, or depression to more serious mental health issues, including rare eating disorders. Some students who have historically experienced serious mental health challenges qualify for special education—but those services were the first to be affected by social distancing restrictions.

Children’s development and learning are shaped by interactions among the environmental factors, relationships, and learning opportunities they experience, both in and out of school, along with physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and emotional processes that influence one another and can enable or undermine learning. There is a large body of evidence showing that when kids lose their sense of equanimity, security, and comfort, they will not do well academically.

If there’s one silver lining, it’s that this pandemic has helped to lessen some of the stigma of mental health challenges.

Wells: I agree with that. The problem now is, how do you access the mental health services you need? Social workers and mental health clinicians are used to screening children in person and doing home visits. Well, they’re not doing that anymore. They need to pivot in how they do their work. AIR has created numerous learning opportunities and products to show practitioners in education and mental health how they can adapt longstanding evidence-based programs and practices to today’s extraordinary circumstances.

Q. Can you describe some best practices for schools and communities in addressing mental health needs of children and parents?

Rider: Best practice for many years now has called for the development of three levels of intervention and support: universal approaches for all students, more targeted interventions for students who share common risk factors, and more intensive support for a smaller number of students who need individualized clinical support and, perhaps, medication therapy. The “multi-tiered system of support” framework provides an architecture for school systems to integrate evidence-based programs that can effectively address students’ mental health, from primary prevention and health promotion through intensive, individualized treatment. Now schools are finding ways to adapt this practice and do it at a distance.

At the universal level, schools need teachers and school staff who can recognize that their kids might be suffering right now. They don’t have to be able to diagnose. Over the summer, many schools trained not just clinical staff, but also educators and the entire school staff—including bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and coaches—in courses like Mental Health First Aid and Youth Mental Health First Aid. They learn to recognize symptoms of a student in distress, how to listen and invite students to share what they’re feeling, and how to connect that student to somebody who knows what to do.

We are seeing school districts that have kept bus drivers and cafeteria workers on the payroll even when their facilities are closed, having them do in-person home check-ins, maintaining social distance. They’re putting their eyeballs on students; talking to them; hearing from them; asking a set of questions to identify any immediate, primary needs; and reporting back to the school counselor or school nurse. Another dimension of universal approaches is screening, asking standard questions that can help schools immediately focus on the subset of kids who are likely to have more significant needs.

We’re also seeing what I think is a best practice right now: Schools are willing to prioritize and focus not on academics at first, but on reconnecting with the children, returning to reassuring rituals, and supporting students’ social and emotional needs.

Wells: AIR technical assistance centers have been right in the middle of developing state-of-the-art school connectedness models. The National Center on Safe and Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE) we manage serves as the U.S. Department of Education’s hub for research-based best practices in student and family engagement and school climate improvement. Our National Center for Healthy Safe Children provides an extensive implementation toolkit and chronicle of lessons learned from more than a dozen years of close work with state and local education agencies implementing cutting-edge approaches that were well-recognized in the final report of the Federal Commission on School Safety.

Many of the districts and agencies I’m working with through NCSSLE are providing both in-school and virtual mental health services. They’re working with parents as well. That’s really hard to do—sitting with a family around a virtual table. It might just come down to access, which is especially hard in rural communities. NCSSLE is working with 27 mental health grantees that have 27 different strategies and methods for implementation.

These are unprecedented times. We are working with states and grantees to adapt hard-won expertise about what works during “normal” circumstances to the radically challenging realities now. While we are providing technical assistance and program support, AIR is also carrying out research and evaluation in high-need schools. It is no exaggeration to say that we are all making history together. Practitioners, administrators, researchers, policy makers, students, and families—the field might well be writing about this for a long, long time to come.