The Student Debt (non)Crisis

Headlines and political speeches about the student debt crisis are everywhere. Googling the search terms “student debt crisis” yields over 19 million hits and the fact that student debt—standing at over $1.1 trillion—exceeds the nation’s credit card and automobile debt levels is getting around. This mountainous debt, we hear, means that students everywhere are failing to launch, living with their parents, or couch surfing while struggling to repay loans. In response, many politicians now advocate debt-free or even free college.

To be sure, a trillion dollars is a lot of money. And some students have accumulated large loans that will be hard to repay. But a recent Brookings Institution paper punctures the overblown rhetoric. Authors Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis called it “A crisis in student loans?” Note the question mark.

The most important study finding is NOT that big loans are swamping large numbers of students. Instead, it’s that, thanks mostly to the dreadful post-recession labor market, large numbers of unsuccessful job-seekers entered colleges with low admission standards (particularly community colleges and for-profit colleges and universities).

Compared to more traditional college students, these students faced more barriers to college success. They were older, more likely to be first generation, and from lower income families—a tough combination that makes completing college or finding a job harder. And the odds against them became even steeper due to their heavy enrollment in open access schools, where low completion rates and bad employment outcomes are common.

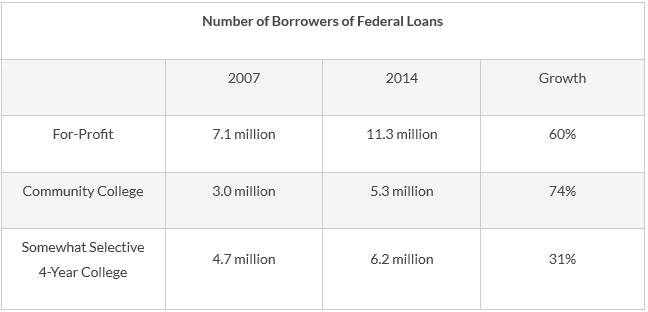

Just look at how much the loan picture has changed since 2007, the year before the economic collapse:

In 2007, just over seven million students in for-profit institutions took out federal student loans, as did three million in community colleges. Within seven years, that number increased by 60 percent for students in for-profits and by 74 percent for those in community colleges. For perspective here, in schools classified by Barron’s as “somewhat selective” (as most regional public campuses are), debt growth was only 31 percent.

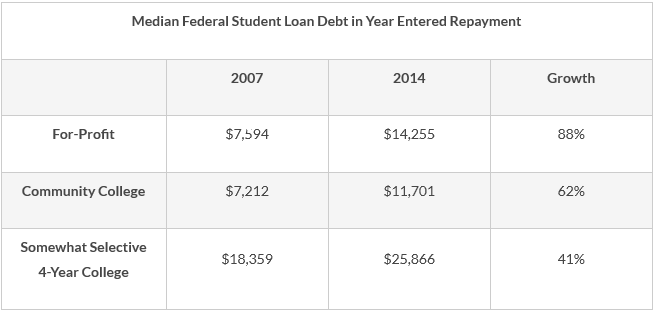

How much debt did these students have when their first loan payment came due? Students in for-profits colleges had around $14,000 in debt on average (up 88 percent from 2007); community college students, $12,000 (up 62 percent); and students in somewhat selective colleges over $25,000 (up approximately 40 percent since the Great Recession).

A debt of $12,000 or $14,000 isn’t the stuff of headlines. But given low completion rates in for-profit and community colleges and both high unemployment rates and low wages among nontraditional students at these schools, debts of this size can be unmanageable.

From these data (plus other analysis in the Looney and Yannelis report), the real story of student debt emerges.

For starters, growing overall student debt—and the repayment problem—is as much an access crisis as it is a “debt crisis,” and the driver is the influx of nontraditional students into open-access institutions. To some extent, this “crisis” is self-correcting. Under constant government scrutiny and relentlessly bad press, enrollments in for-profit institutions are collapsing. And enrollments in community colleges are falling as the job market improves.

But while some negative factors are eroding, many institutions are not doing their jobs. Too many colleges charge too much money for a mediocre education. Colleges are under pressure to cut their prices—and to the extent to which they do that, debt levels should shrink. Beyond that, many colleges are seeking ways to limit student borrowing. Also, students need to know the likely outcome of investing their time and money in postsecondary education before they enroll and borrow. They need fundamental information on the likelihood of finishing, the time to completion, the true cost, and—the key data point—the earnings each course of study yields.

AIR’s College Measures has documented the wide variation in earnings outcomes by credential and program of study so students can determine how much debt they can handle. (The “Know Before You Owe” legislation proposed by Senators Rubio and Wyden and the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard embody this philosophy.)

The push for greater transparency to ease the debt crisis is especially critical for wages at the program level, which tell us much more than wages by college (which is what the U.S. Department of Education’s new College Scorecard data indicates). Some states (with College Measures or on their own) are making program-level wage data available. More states and, ultimately, the federal government should follow suit.

For decades, the U.S. has had the noble goal of making college available to more and more students. But students’ low success rates means that broad-access colleges need to either up their game or fold, and students need to know their chances of success before they enroll—and before they borrow. This path forward entails harder work and more painstaking decisions by students but seems more likely to succeed than costly promises of free college.