Consensus Is Emerging on Teaching Social and Emotional Skills

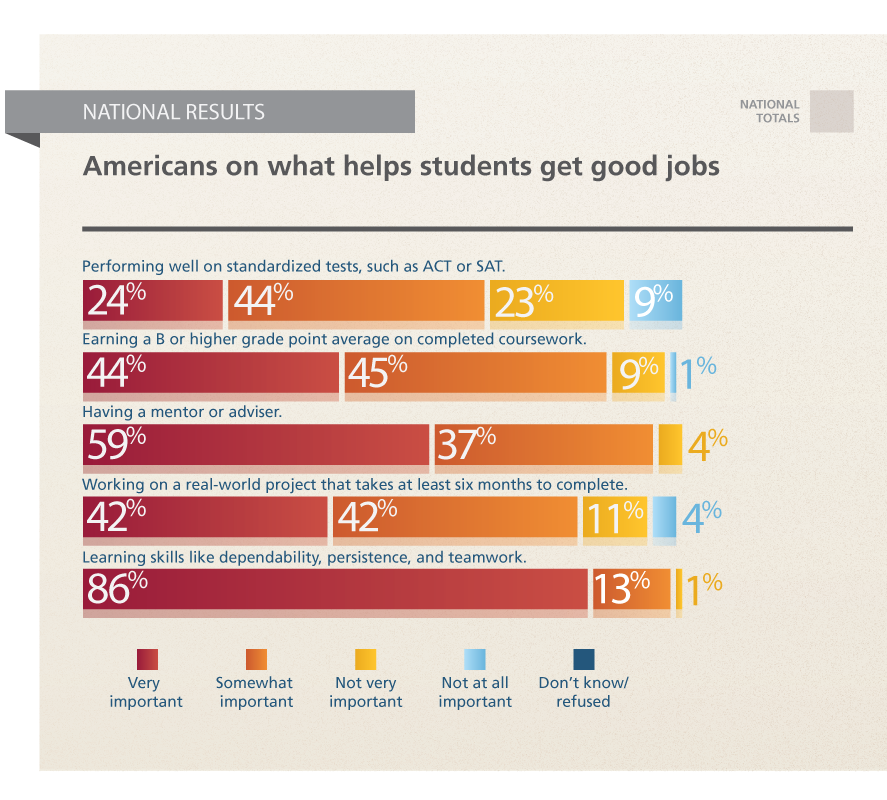

Getting a job is about more than academic performance. Much more, according to a recent Phi Delta Kappa/Gallup poll of Americans’ attitudes about education.

Nationally, 86 percent of adults indicated that “learning skills like dependability, persistence, and teamwork” were “very important” for helping a high school student get a good job one day. In contrast, only 24 percent of adults indicated that performing well on tests, such as the SAT or ACT, was very important and only 44 percent said that having a B average or higher in high school was very important.

The findings mirror an emerging consensus: nonacademic skills—“social and emotional learning”—matter, and schools ought to teach them. Social and emotional skills are personal and interpersonal abilities, such as self-management, social awareness, or relationship skills, which are teachable in school and serve as a foundation for both educational and life success.

There’s a growing body of research on the importance of these social and emotional skills:

- In 1994, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning was established to promote the science, theory, and practice of social and emotional learning in pre-K–12 education.

- In 2002, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills’ framework for teaching and learning included such student skills as creativity, innovation, critical thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration.

- In 2006, economist James Heckman began publishing studies showing that soft skills—such as personality traits, goals, motivations—and preferences create success in life.

- In 2007, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development’s (ASCD) Whole Child Initiative expanded the focus of education from academic achievement alone to encompass children’s long-term development and success while highlighting such issues as health and safety.

- In 2010, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s Deeper Learning initiative began to study and promote students’ critical thinking and problem solving, effective communication, collaboration, and self-direction.

- In 2011, a systematic study of knowledge gained in prior research found that students who participated in school-based programs to develop their social and emotional skills showed multiple benefits, including an average improvement in academic performance equivalent to an 11-percentile-point gain in achievement.

- In 2012, Paul Tough’s book, How Children Succeed, aggregated developing evidence that such personal qualities as curiosity, persistence, optimism, and self-control matter more for later success than such traditional metrics as IQ. The same year, Camille Farrington and her colleagues at the Consortium on Chicago School Research released a review of the research on how nonacademic factors shape school performance.

Public education policymakers and organizations have taken note.

- The 16 school districts that won U.S. Department of Education Race to the Top District grants in 2012 were required to include, for all grade ranges, performance metrics related to a non-cognitive growth indicators, such as physical well-being and motor development, or social-emotional development.

- In California, school districts that received 2013 waivers from federal accountability requirements will base 40 percent of a school’s score on school climate and student social and emotional indicators. Although it is not unusual for teachers to be responsible for their classroom environment, the California waiver is the first large-scale effort to hold schools accountable for the quality of climate and culture.

My own research developing evidence for social and emotional programming in schools and identifying lessons learned includes a 2010–2013 districtwide study in Cleveland. It showed that students improved with an evidence-based social and emotional curriculum, even if imperfectly implemented. An eight-district demonstration project is underway to find out whether, how, and to what end districts can make social and emotional learning an essential part of education. Initial results are expected in 2015. (A copy of the measures of students’ social and emotional competence developed for this study is available at no cost by contacting Kimberly Kendziora, kkendziora@air.org.)

What’s Next?

In February 2014, the White House Office on Science and Technology (with the Hewlett Foundation) convened a meeting to “consider the landscape of what is known about the assessment of the hard-to-measure skills of academic mindset, collaboration, communication, and learning to learn.”

In the next few years, measures will be widely available for schools to assess students’ social and emotional skills. These measures can guide and support practice, moving social and emotional learning from a specialty activity led only by counselors to an integrated part of daily instruction. Soon, the public belief in the importance of skills such as “dependability, persistence, and teamwork” may match what schools actually teach.

Infographic source: Phi Delta Kappa International

Kimberly Kendziora is a principal researcher at AIR. Her work focuses on evaluating school- and community-based programs to promote positive development and support students who are at risk.